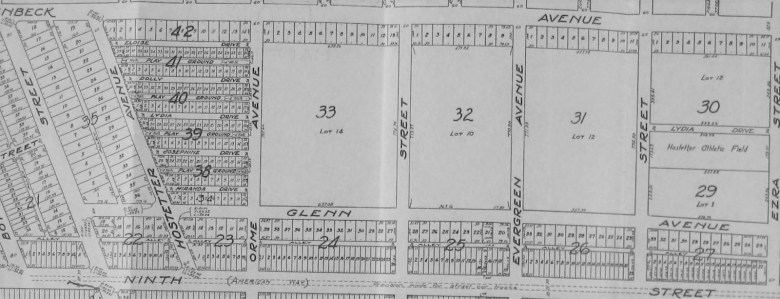

In the southwestern section of Boyle Heights, below where the 5, 10, 60 and 101 freeways come together, is an area that was known as the Hostetter Tract. Subdivided in 1887, when Los Angeles was engulfed in a population and real estate boom often known as “The Boom of the Eighties,” the tract was created by a Pittsburgh industrialist named David Herbert Hostetter.

The Hostetters came to wealth and notoriety because of their “Hostetter’s Bitters,” a product that added herbs (bitters) to gin or whiskey, providing a “medicine” with enough proof (64 or 32% alcohol!) to be popular, not just for whatever ailments it was said to cure, but for a thinly-disguised indulging in spirits.

Hostetter, whose father founded the bitters firm, had a summer home in Beverly, Massachusetts called “Wyvernwood,” but also had a winter residence on Pasadena’s “Millionaires Row” along its famed Orange Grove Avenue (where there are now high-rent apartments and condos). Hostetter came to Pasadena as so many easterners did because of his health and, while he continued operating the family business in Pittsburgh, he maintained his local residence for many years.

A recent article, located by Boyle Heights Historical Society president Diana Ybarra, by Rick Dapp on the South Pennsylvania Railroad, founded in 1882, in Harrisburg Magazine from Pennsylvania noted that Hostetter was, after founder and railroad tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, the second largest investor (others including powerful names like Carnegie, Frick, Rockefeller, Gould and Fisk) in the enterprise. Dapp also observed that, upon Hostetter’s death in 1888, a fortune of $18 million was left to heirs.

Meantime, the firm of Hostetter and Smith was said to have obtained its Boyle Heights property in lieu of payment on a $1,000 debt. Later, it was observed that Hostetter sold the “worst half” of the parcel for some $900,000–quite a return on that paltry investment. Still, for years the tract remained largely undeveloped, although a Hostetter School did open there in October 1898.

By the early 1920s, however, the Los Angeles area was in another of its frequent booms and development was rampant. When it was announced a bridge over the Los Angeles River at Ninth Street was to be built, the Hostetter Tract suddenly became far more valuable. Its 370 acres became highly desirable because of the need to expand the manufacturing and industrial district of Los Angeles from its older center west of the river and east of Central Avenue to locations to the southeast. Later, this included the cities of Vernon and Commerce, as well as portions of Los Angeles like the Hostetter Tract.

Hostetter decided to relocate permanently to Pasadena in the latter part of 1923 and recast the tract as a “high-class industrial district” but also had a vision for a 750-home residential area that would employ modern design, floorplans, and an orientation toward what would become a “garden court” format, in which the fronts of the structures faced an interior court, while the rear of the dwellings faced the street. Hostetter died, however, in late September 1924 before he could act on his concept.

After the estate was settled, the industrial tract, without the residential component, was opened in January 1927. The anchor tenant was Sears, Roebuck and Company, the giant Chicago-based retailer, which constructed its iconic ten-story building at the western edge of the tract and which is now the subject of a major renovation and reuse plan. Other commercial tenants soon followed, but the Great Depression came along within a few years.

Meantime, Hostetter’s daughter, Helene, was married in 1928 to John S. Griffith, a third-generation Angeleno, whose grandfather, John M. Griffith, was a principal in the lumber firm of Griffith and Tomlinson from the 1860s. John S. was born in 1901, graduated from Los Angeles High School in 1919 and ran a gas station for a time before joining the booming bond trading industry in the later 1920s as a partner in Griffith, Wagenseller and Company.

John S. and Helene Griffith lived in a large home in Pasadena designed by the prominent Los Angeles architectural firm of Witmer and Watson and, even in the depths of the Great Depression, Griffith did well in his bond trading business, while his wife’s inheritance at the Hostetter Tract also occupied his time. In fact, by the later 1930s, Griffith left his business and took over the management of the tract full-time.

As the Roosevelt Administration’s New Deal programs took root, the Federal Housing Administration began providing opportunities for funding private housing development and Griffith began to research ways to create such a scheme on the Hostetter Tract. David Witmer, who’d designed Griffith’s Pasadena home, happened to be an architectural supervisor for the FHA program locally and he resigned that position to form a partnership with Griffith.

The project, bounded on the west by Soto Street, on the south by 8th Street (renamed Olympic Boulevard for the 1932 games hosted in Los Angeles), on was called Wyvernwood, after the Hostetter winter home in Massachusetts mentioned earlier, and involved 143 buildings for 1102 apartments on just over 72 acres that would house just under 4,000 people–a scope never before seen in Los Angeles. Griffith targeted middle-income skilled factory and office workers who would be employed within the Hostetter industrial tract and nearby areas under the assumption that the reasonable rents and type of tenant would provide a stability that proved more profitable long-term.

Among the most important features of Wyvernwood was its landscaping. Griffith and Witmer worked with Hammond Sadler, a native of England, who spent two decades with the famed firm of Olmsted Brothers. The Olmsteds, among much else, were responsible for the mid-1920s landscape project at Palos Verdes, where Sadler made his home (and served on the first city council.) Sadler also participated in Olmsted projects at the Bixby estate (now the Rancho Los Alamitos historic site) and the state capitol of Washington.

Later, on his own or in partnership, he did landscape work at U.C.L.A. and private homes in Bel-Air, Beverly Hills and much else. When the City of Los Angeles built the Estrada Courts housing project adjacent to Wyvernwood in the early 1940s, Sadler joined Witmer and Watson on that endeavor. The landscaping at Wyvernwood was, of course, on a massive scale, as 600,000 trees, shrubs, bushes, flowering plants and others were installed, along with lawns, playgrounds, walks and other aspects.

The opening day at the development was 25 October 1939 and 50,000 visitors flooded the site to see Wyvernwood. Only a few of the buildings were done and the 158 available units were rented that first weekend, with rates ranging from about $30 to $45 dollars, depending on the size of the apartment. Surrounding the site stores, schools, restaurants and a movie theater were under development as the area grew.

Within a couple of years, Estrada Courts was completed, though in 1942, when it was finished, it was reserved for defense purposes as the nation entered World War II. In fact, Estrada Courts had its groundbreaking on 7 December 1941, the day Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and led to the American entry into the war. At the same time, the Baldwin Hills Village and Village Green project was being commenced further west and it is considered that the Baldwin Hills and Wyvernwood projects are, in many ways, “sisters.”

In 1950, David Herbert Hostetter died and at the end of that year, Wyvernwood was sold to real estate mogul Harry Jaffe for $5,000,000. As for John S. Griffith, he formed a new firm, Griffith, Walker and Lee, and developed the suburban community of Lakewood, as well as built shopping centers there and at Santa Fe Springs, Pomona, San Bernardino, Buena Park and elsewhere. He was also a principal at several savings and loans (remember those, pre-1987?). Hostetter died a age 78 in 1979.

Wyvernwood has lately been the subject of some controversy as its destruction is being contemplated, while many people are laboring to save it as an important historical element in Los Angeles’ history and as still-viable (if in need of updating) housing. Steven Keylon, a resident of the Baldwin Hills Village and Village Green development, has a highly-impressive series of blog posts on Wyvernwood that formed the basis for much of this post–please click here to read more of his remarkable work.

For some coverage of the proposed removal and replacement of residential and commercial space at Wyvernwood, please click here, here and here. For the developer’s Web site, click here.

Meanwhile, Boyle Heights Historical Society advisory board member Rudy Martinez noted that there is a June 5 event at California State University, Los Angeles called “Storying Wyvernwood” for which there is a Facebook page. Click here for that.

his post contributed by Paul R. Spitzzeri, Assistant Director, Workman and Temple Family Homestead Museum, City of Industry, California.